Fall 2023 Newsletter

By Robin McAtee, PhD, RN, FACHE – Director

Arkansas Geriatric Education Collaborative (AGEC), a Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP) at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Donald W. Reynolds Institute on Aging (DWR IOA)

Wow, I can’t believe fall is here. Summer, as usual flew by very quickly. Activities with the AGEC and our statewide partners are picking up once again as the days get shorter and the nights get a little cooler! The fall semester for our academic partners has also begun and health professions students are once again busy in class and in clinical environments – taking care of our older adults!!

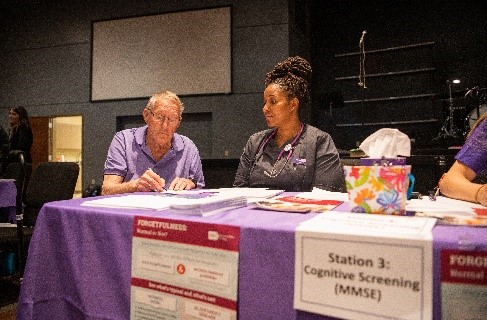

This fall quarter I will be reviewing the final “M” of the age-friendly framework of care; mentation. Throughout this year, we have reviewed the overall concept of the 4M’s framework, the first “M” of “what Matters” (the cornerstone of the framework), Medication, and in the summer, we reviewed Mobility. The last one is Mentation. We all are familiar with the many aspects of mentation, but we will do a quick review as we fold it into our 4M’s framework of age-friendly care!

Mentation has many facets and is very complex as we all know. However, we must do our best as healthcare professionals to prevent, identify, treat and manage any conditions related to mentation including the most common mentation issues with older adults; dementia, depression, and delirium.

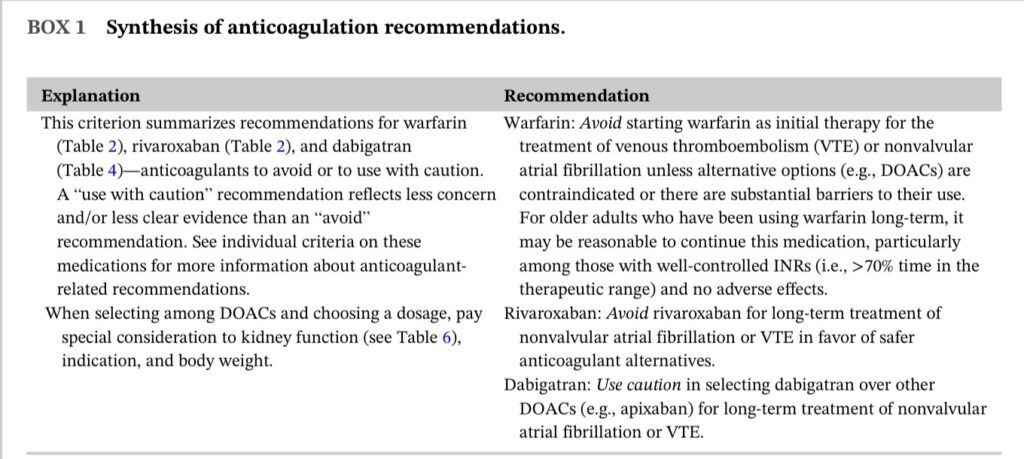

In general, we must support cognitive functioning, independence, and dignity. We must also assess for modifiable contributors to cognitive impairment. This might include chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and diabetes; medications, social life factors, lack of physical activities, poor diet and hydration, extraneous environment factors, excessive stress, lack of quality sleep, hearing loss, and many others. Some are of course modifiable and some are not. But any factor that is modifiable and can be addressed, can certainly affect mentation.

We should also ask them and their caregivers about any confusion, memory loss, or mood changes while considering the requirement for further evaluations. We should also consider social referrals and community type referrals that might address factors such as loneliness, transportation, and dietary needs. Other referrals might also be need to address financial stress and concerns. In summary, many factors affect mentation and many are modifiable. We must ascertain the difference and adjust factors that can improve quality of life and what matters to the older adult.

Again, this was just a quick overview of “Mentation”, and there is a lot more to learn and apply with this “M”, but I hope it helps to inform and remind us to use the 4 M’s and to always consider each “M” within the context of What Matters Most. If you want to learn more, additional information can be found at

https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

If you would like more information or training regarding the 4M’s of Age-Friendly care, please contact the AGEC.