Summer 2023 Newsletter

Darshon Reed, Ph.D.

Associate Dean and Professor of Psychology

University of Central Arkansas, Department of Psychology and Counseling

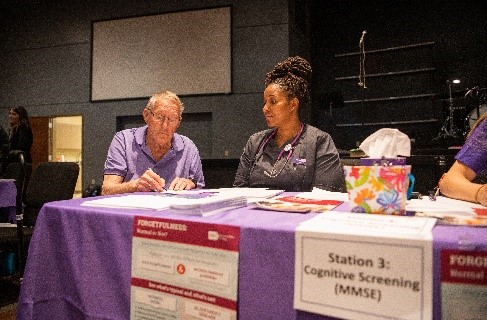

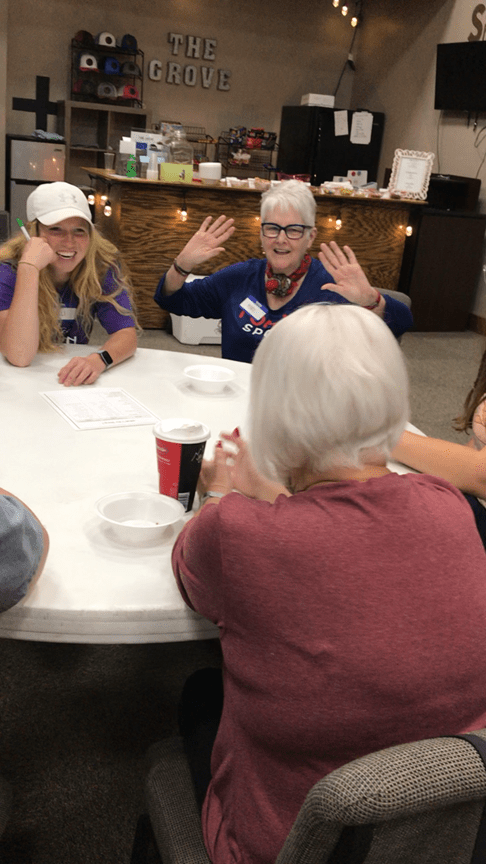

Over 100 UCA students and faculty in the College of Health & Behavioral Sciences (CHBS) participated in a communitywide health fair focused on individuals 50 and older on Saturday, April 15th, 2023. The UCA School of Nursing partnered with Second Baptist Church of Conway to coordinate and host the community health fair, which included a variety of screenings for older adults. The departments within CHBS that collaborated to provide screenings included School of Nursing, Exercise and Sport Science, Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Nutrition, Family and Consumer Sciences.

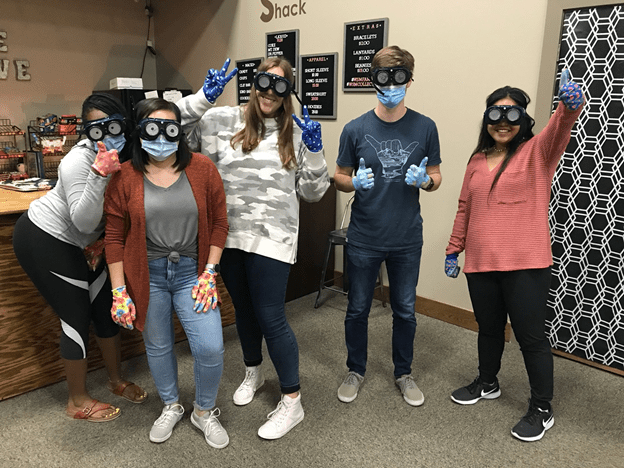

It is vital that healthcare professionals have a holistic health perspective and have the ability to work collaboratively with other healthcare team members. The community health fair’s focus on older individuals allowed students direct access and experience working with the aging population while also providing a learning environment that supported interprofessional education. Screenings included blood pressure, blood glucose, depression, polypharmacy, healthy eating, balance and functional mobility, fine motor, exercise endurance, low vision, and financial literacy. Health fair participants received health passports that included their screening results and were encouraged to share this information with their primary healthcare physician. Those that did not have a primary healthcare physician or who did not have access to care were provided information about the UCA Community Care Clinic housed in the Interprofessional Teaching Center (ITC) at 2200 Bruce Street in Conway, AR.

The ITC offers collaborative and one-on-one healthcare services to the Central Arkansas community. The providers within the ITC are not only practitioners, but also instructors in their specialty fields. Thus, the clinic provides a unique, hands-on experience for students to learn from experienced practitioners and from students within other healthcare disciplines while also meeting the healthcare needs of the community. Follow-up debriefings with students and faculty will occur during the fall 2023 semester to plan for more health fairs for older populations.